Wall Street to Main Street [Essay for Brooklyn Rail]

Sunday, February 26, 2012 at 01:57PM

Sunday, February 26, 2012 at 01:57PM

Wall Street to Main Street [pre-publication draft]

By Paul McLean

"Americans don’t really think that other places are as real as America." [1]

"It is more and more difficult for us to imagine the real, History, the depth of time, or three-dimensional space, just as before it was difficult, from our real world perspective, to imagine a virtual universe or the fourth dimension [la quatrieme dimension]." [2]

Now Main Street's whitewashed windows and vacant stores

Seems like there ain't nobody wants to come down here no more

- Bruce Springsteen, "My Hometown"

1

In my hometown of Beckley, West Virginia’s downtown, “Main Street” is several streets coursing square-wise through Beckley’s nucleus. One of the streets is Main Street. Downtown for me was an afterschool and weekend destination, and I was willing to draw a few dollars from my dad’s wallet and dodge bands of hellions to get a burger at Fred Yost’s diner, comics and candy at the newsstand, or window-shop for guns and knives at the pawn shop. After I moved away Richard Haas was commissioned to do a trompe l'oeil painting on one side of the Federal building there. Like the Peck Slip one between Front and South streets here. I interviewed Richard once for an art radio program I hosted in Nashville. He talked about artists “looking at the same thing we’re all looking at, but looking at it so differently.”

I would suggest that American artists look at Main Street, the same way you look at a sunset.

2

Paul Goodman’s book on American youth got it wrong, on account of Main Street, which is not an absurdity, on its face, or façade, Disneyfication notwithstanding. Anarchists generally get Main Street wrong, because the Promised Land that Main Street infers in Main Street’s place or capacity as gateway to the American Dream is already occupied territory. Ask the natives. Even if the Main Street now consists of vacant stores mostly, Main Street is still properties along a thoroughfare, a set of developed plots in the ownership schema. This is problematic not only for the community, but for the local Chamber of Commerce, which shouldn’t be confused with the ALEC-pushing US CoC. If or when the compartments lining Main Street are not currently occupied by tenants, a basic function of the society breaks down: local exchange; and not just the exchange of goods; also the basic, face-to-face social exchange, the ties that bind – the centering intercourse in our free speech continuum. If you connect the dots, you’ll get to why surveillance state cameras are so corrosive, and Miranda rights so important. Tyranny hates a corner market on Main Street, because that meeting place in a community exists as a shadow or casual town hall.

To reframe the impetus of anarchic reformation of the various sects of neo-protestants, of both camps – Capitalists and their anti-paths - Squarification, and the re-occupation of the square, are problematic in the USA of democratic main streets (which should not be conflated with either of the camps, vying relentless for just that obscuration), where we are passing through or stopping for a piece of fresh pie and some company. In towns like Catskill, New York, or Beckley, West Virginia, and thousands of others like them, the proposition of hanging out on Main Street is more a ghost-hunt now and phenomenologically like a William Kennedy (b. Albany, by the by) Ironweed-esque reverie. It is for the local an animated imaginary in very slow motion, a confrontation not with a fabricated nostalgic image, but with a very real and personalized episode of loss and despair, of creative obsolescence, waste and abandonment.

This individualized mind-screen cinema of uninvited absence, the dream of a futureless home, has replaced Hollywood, and the game machines will not satisfy as a distraction for too much longer. People lost in empty architectures and unfunded community plans are today the pervading 99% community dynamic, not of change or hope, but of self- and collective-consuming entropy. We should acknowledge the winners in this drama. The destitution of Main Street is always the legacy of extraction and exploitation processes. The 1% switch residences like suits.

The tough comeuppance for the rest of us is that the Ghost Town is today Our Town. When we or our towns are left behind, by whatever new market dynamic has emerged to which the marketers can attach the ubiquitous fanfares, whichever “New World” the neo-robber barons zoom off to conquer and order, we The People are left to fend for ourselves, or feed ourselves, or on ourselves. What do the Giants of Industry care? They are, after all, artificial people.

If Occupy Wall Street doesn’t figure out how essential Main Street is to a sustainable and meaningful life for so many 99%ers, and OWS likewise fails in the suburbs, where Main Street has been brutally displaced by the mall, then the Big Box, or an urban-planning-invented version of itself, the movement is lost in America. A word of advice: We don’t need to be reminded that the American Dream isn’t real, not since Hunter Thompson wrote about it in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, giving it a mad destination, stopping well short of the continent’s end. Baudrillard picked up the thread from there, pointing at the horror behind Main Street, Incorporated’s black eyes floating above the happy black smile on a perfectly round yellow background.

The stakes are huge, and the 1%ers not only recognize that, they are using every means at their substantial disposal, such as ALEC and Citizens United, to tilt the board their way. The best thing Occupy has going for it is the desperation and righteous indignation of everyday people - which is to say, most of us- who have been relentlessly screwed by the greedy and the big corporations the 1% control. The second best thing OWS and the rest of us have going for us is that the 1%ers can’t help but underestimate our chances, and our resolve to be free of their oppression.

3

Main Street, USA is a myth that’s real, but moving. Essentially, Main Street is a plaza or town square, not constructed as a square, but as a linear proposition. “Main Street” is also the stuff – buildings, people - that accumulates along the through-put, the artery, which passes into and out of the community whose main street Main Street is. A town with a Main Street is a town without a center, really. The town center with a Main Street is probably determined in the abstract as a median point between the edges of the in and out marks on the road transiting through the town, called Main Street. That is, downtown on Main Street is the halfway point between the borders of the Main Street town. Not actually a center, though: the center has to be superimposed, like on a radial map.

Much of American drama, in literature, theater and cinema, is predetermined by the parameters of Main Street in a given or imagined American town. Who controls Main Street? Who guards its borders in and out? How does the town change, when a stranger passes through (via Main Street), or decides to stay? And so on. The context is usually about permanence and impermanence. “Are you coming or going?” is a Main Street interrogatory. “How long have you been here?” is the sort of question a stranger passing through might ask, not someone’s question who has never exited through the borderline to whatever might be, beyond the town of Main Street.

Bruce Springsteen got this. Hollywood got it in its early years, but since then has twisted the road from Main Street to stardom into a bitter and cancerous labyrinth of abject folly. When I think of Main Street in American literature, I think of Sherwood Anderson, of Winesburg, Ohio. In some crucial way, the human condition in relation to Main Street can be reduced to a hero-grotesque conflict, but this is not correct, or exhaustive. On the Road of Kerouac, eventually blew open the boundaries of Main Street America.

In art, Pollack mapped Main Street USA, not as a straight line, but as a massively dimensional folding of space and moment, the hero of painting simultaneously its gross monster. I would also add Don Judd’s Marfa to my Main Street recounting, and probably most of Cormac McCarthy’s stories. In the domain of Main Street, we have a swirling confundament of heroes embracing the grotesque in a frightening dance (McCarthy’s Judge in the final scenes of Blood Meridian) and the women – mostly now in black and white - who longed for the stars beyond the edges of their strictures, for Hollywood, mean boulevards and bad outcomes, or no, or no matter.

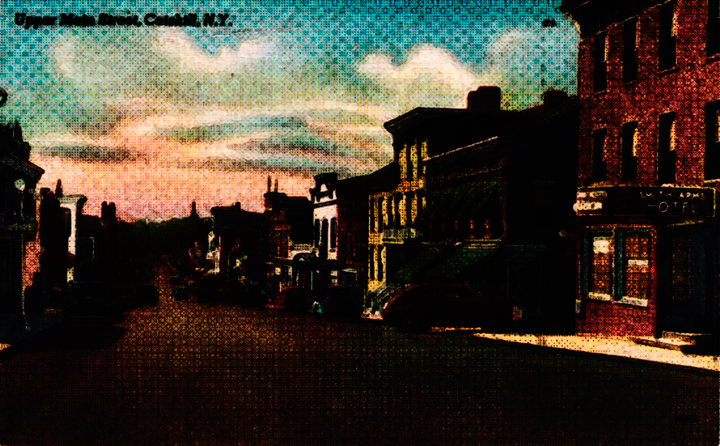

Eventually, however, we have to bring it back home to the Promised occupied Land, of Thomas Cole, whose National Historic Monument in Catskill, NY doesn’t own a single one of his paintings. I heard that every once in a while they can borrow one from an owner to display.

Source data - USGenWeb Archives; Digital processes - PJM

Source data - USGenWeb Archives; Digital processes - PJM

4

Some of the best portraits of Main Street have come to us on postcards. That should tell us something about the nature of it. There’s something about Main Street we want to send ahead of us or behind us, a flattened or idealized iteration of this live scene, speeding past, coming towards us. The car made Main Street work, to a degree the train, boat and buggy did not succeed for the High or Front streets. The freeway changed Main Street even more, for the worse, bringing with its speed and distance McDonald’s. For Main Street, there is nothing worse than a by-pass. The only thing worse is when the local oil well or factory goes dry or taps out. We’re talking a death sentence for a town relying on traffic and commerce for and by strangers.

We have some representation issues, too. Thomas Kinkaid gets Main Street, for the folks. That much is inescapable. For this reason Kinkaid is relegated to the marginal mainstream by the Avant Garde, and along with Bob Ross, these painters of light and lite give the AG the willies. Kinkaid paints Main Street, not as a desert of the real, an ironic vacancy, but as a projection of non-targeted romantic longing, empty of relational entanglements and contingencies, like parking tickets or VD, an unwanted cost of visiting too long or in the wrong receptacle/on the wrong protrusion. The antipathy Kinkaid generates among vacuous artsies, when he’s acknowledged at all, is a peculiar rupturing force related (dimensionally), I would argue, to the buffalo holocaust of the 19th Century, which yielded only huge piles of bone and eventually a dust storm the likes of which this nation hasn’t seen before or since (yet). We have to face facts. Main Street today is mostly a wasted carcass, like a buffalo killed for its coat and maybe some chew- or cooking fat.

5

Is there a solution? If we permanently fall in love again with Main Street, desiring to be native, not as occupiers, but as a population whose locus exists for commonwealth, we may magically be able to revive our towns, despite their mortal wounds, the same way Neo did Trinity in The Matrix 2, and vice versa. The vice versa is the key element, I believe. It’s a long shot, sure, but we don’t have much else, short of global revolutionary warfare, left. Perhaps the movie, one movie, in its digital dreaming, offers an answer to the brutal mechanisms of the lurching, wounded and morally bankrupt corporatized Dream Machine, or to put it more correctly, the anti-dream machines, which run on odds like the lottery’s.

At least, if not a solution, that is a promise, whether real, realizable, or not. A Main Street milagro.

If Main Street is to be re-centered as the dreaming nexus for our town, we will need an app for that. As William Least Heat Moon mapped it for us, we may need to take Blue Highways to get to the Red Ones, meaning our nativity, and a new formulation of our place amongst each other, not as Others, but as a conjoined or unified people, and that trajectory will certainly pass along Main Street through America’s “Heartland.”

A point of clarification: A Heartland is never a Homeland, as the latter in modernity operates as a security blanket of deceits, protecting our town from any imagined or perceived Terror. If we are to re-envision a Main Street, our new model will need to be free of fear of what and who exists outside our borders, and art is an app for that. Art doesn’t have borders. It has a frame.

Even more important, our new Main Street America will need to provide some relief from the fear that permeates the town made of homes wired to networks that depict one’s neighbors as the Enemy, as serial killers, as perverts, as monsters, as the grotesque. The longest trip right now for Americans is the one from one’s living room out the door and down the street, to our common space. That path is the most neglected one. People are afraid of what’s “out there,” when they fill their “in here” with horrors, real or fanciful.

6

What can artists do for Main Street, given that 99% artists (and Main Street) won’t in the near future be getting more than subsistence funding, if any at all, from corporations, anarchists, most 1%ers, the State, the Church, or the otherwise occupied and fearful, just-hanging on/out/in there Reality TV-absorbed and variously addled masses, for whom art is a just a luxury item, anyway?

[From our Wall Street to Main Street prospectus, in which we propose a new model for Main Street arts and culture, which is the imagining of a sustainable program for 99% or 100% arts and culture as an ongoing, progressive production, this is the project narrative]:

On September 17, 2011, responding to a call to action published in the magazine Adbusters to Occupy Wall Street, a motley crew of activists, artists, and idealistic youth converged on Zuccotti Park in the financial district of Manhattan, and a movement was born. Over the next two months Occupy Wall Street focused the world's attention on the grievances of the 99%. A David versus Goliath drama unfolded, as the numbers of Occupiers swelled, occupations across the nation and around the globe formed in solidarity with OWS, and the Occupy bands encountered coordinated opposition from police, corporate media, government officials and the 1%. Since then most of the occupations, including the one in New York City, have been dispersed, sometimes peacefully, sometimes with brutal force, but OWS has proved itself to be an idea that cannot be evicted.

On the six-month anniversary of the occupation of Wall Street, in scenic and historic Catskill, New York, Occupy with Art and Masters on Main Street are working together to present a dynamic series of arts projects, events, cultural and educational programs to look back at the often stunning visuals and iconography of Occupy, to get at the grievances driving the protests, and explore ideas and solutions for improving society for the 99% - one person, one community, one Main Street at a time. In keeping with the spirit of OWS, and featuring art by OWS artists and images documenting the global movement, Wall Street to Main Street will showcase a wide range of expressive media, ideas and creative approaches. Wall Street to Main Street also will provide plenty of opportunities for people to participate in the fun and exciting activities slated throughout the exhibit run.

The artists participating in Wall Street to Main Street range from the famous, infamous, anonymous; local, regional, national and international. The media range from the latest in digital technologies, such as Augmented Reality (AR) to the conceptual, the performative and the traditional. The content ranges from in-your-face to lyric, from contemplative to witty, from the documentary to the imaginary. What unifies all the artists and artworks is situational. How does each exist in relation to a specific time and action (Occupy Wall Street)? Can creative responses to OWS such as these, like signs, be re-situated, woven into the community fabric of Catskill, a real 99% Main Street town? One thing about Wall Street to Main Street is clear. Whether redressing grievances, expressing liberty - personal and/or aesthetic - whether calling for solidarity - political and/or economic - the projects on view in Wall Street to Main Street, the performances, talks and community activities combine in a powerful proclamation that Occupation is local and global, simultaneously.

In addition to the rolling exhibits and programs Wall Street to Main Street will offer the town of Catskill, the Hudson Valley region, and destination visitors coming to see the show, several very special projects will help us re-examine art for the 99% in a fundamental way. For "The People's Collection" project, everybody who lives in Catskill and nearby will be invited to bring an object he or she loves from home to display in a designated storefront space on Main Street. Another project of note, the format of which is still being worked out, is "Suggestion Box," which will encourage the folks of Catskill to share their "two cents" about the status quo and how it can be made better. When combined with world-class exhibits like the one curated at the beautiful Brik Gallery by Geno Rodriquez, former director of the Alternative Museum in New York City, these expressions of the 99% will likely be great conversation starters, and in some important ways begin to shift what we think art is in a direction that will be more democratic and inclusive.

7

Late last night, in the howling wind and rain, I was smoking on Bloomberg’s sidewalk in Bushwick, which to my knowledge is currently devoid of a functional main street. I was close to Bushwick’s main street approximation – Knickerbocker – pondering the narrative between paragraphs, when one of my building-neighbors, King, climbing out of his ride, stopped to share a stogie with me, on his way to bed. He asked what I was up to at 1AM, and I told him, writing about Main Street. He replied, in appropriate Brooklyn-ized fashion, “What about the Mean Streets?”

If we don’t do anything about Main Street, that’s exactly what we are left with. 42nd Street in the early-/mid-80s, pre-Ghoul-iani, pre-Disneyfication, comes to my mind.

[1] Jane Jacobs, interviewed by Jim Kunstler for Metropolis Magazine, March 2001 (September 6, 2000: Toronto Canada; http://www.kunstler.com/mags_jacobs.htm)

[2] Jean Baudrillard, "Disneyworld Company," Liberation, March 4, 1996 (http://www.uta.edu/english/apt/collab/texts/disneyworld.html)

admin |

admin |  Post a Comment |

Post a Comment |