Fallacies of Hope: Borodino, Culloden and the Slaver Ship Zong

Saturday, May 11, 2013 at 09:02PM

Saturday, May 11, 2013 at 09:02PM By Paul McLean

Introduction

{[HE]|[R]||[E]|||}

“Aloft all hands, strike the top-masts and belay;

Yon angry setting sun and fierce-edged clouds

Declare the Typhon's coming.

Before it sweeps your decks, throw overboard

The dead and dying - ne'er heed their chains

Hope, Hope, fallacious Hope!

Where is thy market now?"

[J.M.W. Turner]

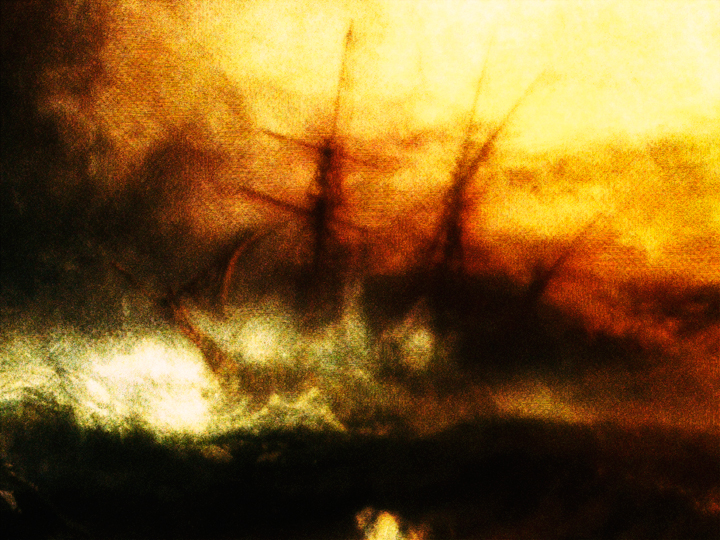

When preparing for an exhibit, I do research. Nowadays, that often involves little more than typing some words into the Google search engine, and then clicking on the appropriate Wikipedia entry at the top of the results page. I did that. I can’t remember now, why or how I came across J.M.W. Turner’s painting [see image above], and what exactly about it inspired me so, to the extent the name of my SLAG exhibition derives from the poem extract Turner posted next to his painting when he first showed it (according to the Wikipedia entry) at a meeting of the British Anti-Slavery Society in 1840. I must admit that prior to the encounter with “Typhon” Turner wasn’t very high in my rankings.

I believe I had been thinking about slavery in other terms last fall, thinking about slavery in its modern variations, which involve a clock, information and management - not manacles and massacres - as a general rule (although let’s not be so naïve as to imagine the cruder type is eradicated – the power dies hard). Whatever, I could go on about the re-packaging of slavery at length, and have elsewhere, but this is an artist statement, not a manifesto. Suffice to say I became – not obsessed with – “fascinated” or “inspired by” are better – [__________] – (let’s say) awakened to Turner’s slave ship painting, about which Mark Twain wrote:

"What a red rag is to a bull, Turner's "Slave Ship" was to me, before I studied art. Mr. Ruskin is educated in art up to a point where that picture throws him into as mad an ecstasy of pleasure as it used to throw me into one of rage, last year, when I was ignorant. His cultivation enables him—and me, now—to see water in that glaring yellow mud, and natural effects in those lurid explosions of mixed smoke and flame, and crimson sunset glories; it reconciles him — and me, now — to the floating of iron cable-chains and other unfloatable things; it reconciles us to fishes swimming around on top of the mud — I mean the water. The most of the picture is a manifest impossibility — that is to say, a lie; and only rigid cultivation can enable a man to find truth in a lie. But it enabled Mr. Ruskin to do it, and it has enabled me to do it, and I am thankful for it. A Boston newspaper reporter went and took a look at the Slave Ship floundering about in that fierce conflagration of reds and yellows, and said it reminded him of a tortoise-shell cat having a fit in a platter of tomatoes. In my then uneducated state, that went home to my non-cultivation, and I thought here is a man with an unobstructed eye. Mr. Ruskin would have said: This person is an ass. That is what I would say, now." - "A Tramp Abroad," Volume 1, Chapter XXIV, via Wikipedia, via Project Gutenberg

∞

After doing research, I engage in a phase of verifications. So, I visited “The Slave Ship” at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. The painting’s a popular attraction in MFA’s permanent collection. I looked at it for about fifteen minutes, while my wife and infant son, my brother and his wife and kids, patiently waited. As I recall, my feet were sore and one of my “wisdom” teeth ached. It was the day after Thanksgiving, 2012. I shot a few pictures with my mobile phone and we moved on. I had already downloaded and compared a selection of virtual versions harvested from the web. The computerized reproductions varied a lot. It really does matter, seeing the original, if possible.

We were going to Fanueil Mall/Hall afterward for dinner, so my Turner reverie was brief. Plus, several in our party wanted to take in the fashion photography show in the museum’s basement. Why not?! A few days later, returning to Bushwick, I developed some digital images with the photos and wrote a poem (“Fallacies of Hope”) I performed at the Occupational Art School poetry reading “Starr Street Slam” at Bat Haus, accompanied by Wilson Novitzki, my partner in DisciplineAriel, and New Media diva Amelia Winger-Bearskin. Reworking an image digitally, and writing poems about them, adds a curious intensifying and magnifying quality to my sense of the original. Philosopher-colleagues like to call it “close reading.” I think of it more like film processing – dodge and burn! Not to imply I have much direct experience with film processes – I use Photoshop and trust the film to the professionals.

∞

If you are unfamiliar with the story that inspired Turner’s painting, the slave ship Zong in transit with a cargo of slaves encountered a storm that threatened the vessel. The crew determined the best course of action involved casting over a hundred of the slaves overboard to their certain deaths. The losses would be covered by insurance.

∞

I like that Turner generated multiple names for this painting [“The Slave Ship,” “Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and the Dying – Typhoon Coming On,” “Typhon” and the corrected “Typhoon”] and that he displayed the painting repeatedly, in multiple contexts. I also like that prominent art writer and presenter John Ruskin was a big advocate for the painting, and, as noted above, that Mark Twain, an ancestor on my mother’s side of the family, was a witty critic of it.

Over the past few months, I’ve been wondering what my show “Fallacies of Hope” would be about. People at contemporary art shows often ask what a show is about, because the meaning often is not very clear. Sometimes nowadays shows have no explicit meaning at all. I like to have a prepared answer for about-inquiring minds. So here it is:

“Fallacies of Hope” is 1) about defeat, and so, of course, it’s going to be about fighting. I guess that means it’s also about victory and not-fighting, too, since you can’t have the one(s) without the other. & 2) Freedom.

The Slave Ship is not the best defeat/victory or fighting/not-fighting painting, you might argue. I would agree with you. It speaks to the second about-concern, which is Freedom. So, I came up with a couple of secondary references that I hope will be more illustrative of victory and defeat. One is “The Battle of Culloden” by David Morier. The other isn’t actually a painting, at least in the first order reference. It is the Borodino sequence in the third part of Sergei Bondarchuk’s cinematic epic War and Peace (1968). Although I would at some point like to discuss the second order reference, which is Franz Roubaud’s epic panorama painting of the battle, and maybe the Avon Napoleonic Fellowship’s 2012 war-gaming version, too.

∞

Battle of Borodino, fragment of panoramic painting by Franz Roubaud

Battle of Borodino, fragment of panoramic painting by Franz Roubaud

I recently watched the popular Hollywood movie Lincoln, which seemed to me to be more a movie about the abolition of slavery in the United States during the Civil War, than a movie strictly about the President. “Slaver Ship” and the Spielberg’s bio-pic strike me as creative efforts contributing to the defeat of slavery in Britain and America, respectively. How are they different? Well, Turner’s painting apparently contributed to the success of the movement at that time. Lincoln is a narrative film about historical events a century and a half in the past.

I also recently watched the popular Tarantino film Django Unchained. I think it’s too cinematic to be of use in this paper. It stays in its medium, marvelously.

As the research phase for “Fallacies of Hope” continued, I added a couple more kernels to the data gumbo, namely the battles of Borodino and Culloden, as I said, because the show is about two (binary) subjects [War & Peace]+[Slavery & Freedom], and I needed fodder for the war and peace part. Haha.

I’ll only gloss over these historical events here. As I said, I came to Borodino this time via a film, Sergei Bondarchuk’s epic War and Peace (part three). I went through a fairly extensive phase of Napoleonic research in my teens, so the subject was not entirely unfamiliar. Back then I was painting military miniatures, including some from that period of European war-history. The soldier’s uniforms were brilliant! I didn’t really participate in gaming. I was happy with the study of tactics and the models. I got the impression that Borodino wasn’t given the same weight in most of the general Napoleonic histories compared to Waterloo. Probably because Russia was so problematic – there was a Cold War, don’t you know! It was around the time Reagan hit the scene. Lots of bold rhetoric in the news… A tectonic shift in the political topologies of the world was in the making. The super-power binary was collapsing. New threats were emerging, as in the case of Lebanon. [See, context.]

By the way: In my research I discovered that even though Bondarchuk’s War and Peace was in the public domain, and it is one cinema’s major epics, maybe its greatest, Google and YouTube make it awfully hard to find online, much less to watch it free. “The Search stops here!” (at the paywall) seems to be the apparatus. I suggest this phenomenon bears further scrutiny, given the substantial consolidation of copyrighted movie and television content in pay-schemes on the web. When it comes to some kinds of culture, the Information Superhighway is beginning to look less and less like a freeway and more like a highly but subtly constructed toll road.

Screengrab, Bondarchuk’s War and Peace

Screengrab, Bondarchuk’s War and Peace

The story of the Bondarchuk movie is I would argue as compelling as Tolstoy’s (the one in the book, and the one of the book), and as compelling as the battle itself, which involved nearly a quarter of a million men and tens of thousands of casualties. Borodino was the turning point for Napoleon, arguably, and it was a “victory,” although in hindsight the case can be made that the battle’s outcome was Pyrrhic for the “Little Corporal” (the affectionate nickname given Napoleon by his men). I incidentally compare the situation of Borodino in effect to the infamous incident of President “W” Bush landing on the aircraft carrier to declare combat operations in Iraq to be over. Victory in war is often not what it appears to be.

The long Borodino sequence in Bonarchuk’s War and Peace culminates in a spectacular sweeping shot of battleground carnage. Ultimately, the camera finds Napoleon atop his steed, grimly surveying the bloody field, amidst hundreds or thousands of corpses. This is not Napoleon in the famous David painting. The voice over, drawn from the original text, assigns a powerful moral determination to the scene, and to Napoleon, who the disembodied voice explains, bears the heaviest weight of responsibility for the war and suffering playing out in the movie, the book, and history. It’s one of the most impressive cinematic moments I’ve ever seen.

I watched the movie on YouTube [overcoming the technical subterfuge, thanks to Open Culture (http://www.openculture.com/freemoviesonline)] unfortunately, so the scale of it was problematic, I should say. At least it was free. I discovered that the original movie cost something like $100,000,000 to produce, and the production took several years, required a cast of thousands (including the Soviet army), and was celebrated for great attention to historical detail in production design. The filmmakers loved the soldier’s uniforms (and costumes) as much as I did, evidently! The production was really true-to-life.

I’ll be honest. Bondarchuk’s great cinematic achievement sparked an association in my thinking with America’s Civil War re-enactors. I’ve been wondering about the latter a lot, thanks to study of the late American painter Manning Williams’ life and art, and my friend Dane Carder’s painting and photography series emerging from the subject. I found other contingencies. One, mentioned above, is the great panorama painting of the Battle of Borodino by Franz Roubaut, completed a century later, and housed in a museum in a Moscow suburb. The canvas is 115 meters by fifteen meters, and the presentation features actualities (dioramic elements) and a soundtrack. The last I’ll mention comes to me via the web, and probably will strike the reader as an odd inclusion, except for my earlier autobiographical note (the one about military miniature painting). A wargaming club, The Avon Napoleonic Fellowship set up a Borodino game, commencing 200 years to the day after the event of the original, “albeit about 12 hours later than the beginning of the battle on that fateful day in 1812,” according to the site blog. The gamers’ military miniatures numbered around 5,000, and the play took three days to complete. Here’s a passage that reflects the commitment and passion of ANF in their recreation of the Battle of Borodino:

As regular readers of this blog will know, we had been planning and preparing this game for months. All of the time that went into it, including the three days of playing the game, were well worth it.

I’d like to make special mention of Mark’s efforts to make this game possible. For him this game was over 30 years in the planning. It would not have been possible without his superhuman effort in painting the extra Russians that we needed for the battle. He painted about 900 figures in six months, peaking at nearly 100 in a week!

Wow!

∞

'Battle of Culloden" by David Morier

'Battle of Culloden" by David Morier

The citations for Culloden, as an influence on “Fallacies of Hope,” aren’t nearly as impressive for most readers, probably, as the ones cited above. The 1965 movie about Culloden, unlike Bondarchuk’s costly rendition of Tolstoy’s War and Peace, is not an epic scale moving image version of a great historical episode. It was a boundary-blurring historical documentary by Peter Watkins, very much in the spirit of the times, inspired by the popular book by John Prebble titled Culloden. I found this excellent quote from the movie at the IMDb (Internet Movie Database):

Narrator: They've created a desert and have called it "peace".

I’ll focus here more on Prebble than Watkins, and only briefly, although the influence on Fallacies of Hope by Prebble probably requires a more thorough treatment. Prebble is known for scripting Zulu, a war movie that pertains to the narrative here probably as much as any. Prebble was a controversial author of books about the massacre of Highlanders at Glencoe, the Clearances of Highland Scotland, and the one about the ill-fated conflict at Culloden. His books were “ferociously” attacked by the professional historians of his day as a type of “faction” [for elaboration, see the excellent, if to my mind problematic, obituary for Prebble penned by Steve James in 2001, which appears on the World Socialist Web Site (http://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2001/03/preb-m21.html)].

I discovered Prebble’s books during a 1995 honeymoon in the Highlands of Scotland, which also turned out to be for myself a powerful and emotional homecoming to my ancestral roots. The Prebble books (and others) became important references in paintings I produced and showed over a subsequent two-year span, in Scotland (in Edinburgh and on the Isle of Skye, and in Nashville, upon returning to the States). I can only begin to convey the impact they had on my experience of Scotland, views on identity and artistic process. The resonance sustains to the present. In one concept for “Fallacies of Hope,” I visualized the Dim Tim paintings configured as diptychs with paintings from my Scottish series, which were titled “Where My Feet Stick to the Ground” and “My Own Private Glencoe.”

I should mention that during our several-month sojourn in Scotland, the Stone of Destiny was returned to Edinburgh Castle, and protests (I participated in one) took place, for Scottish Independence from the United Kingdom. The English called the prospect of Scotland’s shearing off from the UK de-evolution or devolution. I find that term to be telling. I think this is relevant now to share, because in 2014 Scotland will vote to either remain in the Union or be free of its Southern neighbor, through a complex negotiated process of controlled withdrawal. So, as subtext, the arc of the minor narrative (of Scotland’s freedom) is, without too much notice, approaching a potential resolution. Will the vote succeed where the Claymore could not?

∞

If I could inject a crudity: Historical moments are dimensional. It seems intensely necessary to mention Baudrillard at this point in my statement. I’m positive this must be terribly confusing and disorienting to the reader. I understand an artist statement is meant usually to accomplish the opposite effect. Maybe I should plan on supporting this text with artist talks during the course of my exhibition, support the historicity with orality. I’ll try to connect the dots, between the civilized confabulations with the tribal versions and digital compressions, though, in due time. For now, let’s imagine the paintings in “Fallacies of Hope” in context, as just so much more content, as suspended volumes in space, and not, simultaneously.

I suppose the goal is to achieve a sort of fine symmetry, something dynamic. Which reminds me of my last referential entry in this introduction to “Fallacies of Hope:” the paintings of Bellows that were recently exhibited at the Met in New York City. Of course I was interested to see the boxing paintings, which are high in my rankings. The surprise came with my encounter with Bellows potent and stylized depictions of the Germans’ atrocities in Belgium during the First World War. Although I found many gems in this retrospective, some of which, even most of which I could relate to the Dim Tim body of work, none packed the impact of that cycle of very disturbing paintings and drawings. It’s not everyday we confront representational brutality of this vigorous nature. It’s not a commonplace experience for most of us, to witness soldiers carousing with babies on their bayonets. Except where it is.

1

In her introduction to Art and War, Laura Brandon asks the right question. “What is war art? And answers:

Out of curiosity, as I began writing this book, I looked for “War Art in my 1986 edition of The Oxford Companion to Art. There was no such entry. Instead, I found the subject under ‘Battle-Piece’. I next turned to the Internet: the thousands of listings I found there suggest that ‘war art’ is now a common term. Undoubtedly, this newfound identity is one reason for this book’s existence. It is the first to look at the topic internationally through time as more than battle pictures, an aspect of national history, or military illustration.

Yet the field of war art is immense and worldwide, somewhat akin to religion in the way war inspires people to create in order to understand. Countries foster war art in the interests of nation building, and it exists in all societies and cultures.

To figure out what “Fallacies of Hope” is about, we have ask other “right” questions:

- What is art?

- What is peace art?

- What is slave art?

- What is free art?

- What is media?

- Who are we?

And so on.

“Fallacies of Hope” in its range of contextual notations and content associations does not really have a “start” and “finish.” It doesn’t represent a closed system. It isn’t about an event, per se. “Fallacies” is a dimensional spatial occupation, which means it contains a finite set of elements (located in a specific time and space) that indicate an infinite set. The medium, the show’s metaphysics, is choice. The objects presented in the show offer choices that in themselves imply an infinity of other, possible choices or directions of unfolding.

∞

The Introduction to this text suggests that the paintings and other artworks in “Fallacies” emerge from the artist’s broader concerns: a convergence of the means of expression, all of them, including those enabled by evolving mechanical devices, technologies of the hand and the eye, energized by electricity, amplifying, intensifying, illuminating. If some of them, like film, rely on illusion, so be it. The camera blinks and we believe the image moves. The camera winks and we believe we have a moment captured as a soundless, motionless representation of reality, a product of the shooter’s unique perspective. The Internet, its databases and transmissions, convince us that a compressed version of our expressions or thoughts is good enough, for now. Fine.

Art can and does supersede the regime of the artificial means, repeatedly, and the aim of “Fallacies of Hope” is to verify the failure(s) of “creative destruction.” Cloning is as impossible as AI, and the original once more holds its own, which in summary is “us” – ourselves; our value(s) and our mean[(-ing(s)].

Maybe I’ll perform a recitation of each story of each painting in “Fallacies of Hope.” I toggle between one position, advocating transparency in production, an open source mode, one that demands that every component of the project is described in detail and shared as a gift; and another position, one insisting on the secrecy of inception, a cohering to universal law, which seems to require that origins remain mysterious. Both positions seem, ultimately, to be flawed. The problem is that neither concept nor object can be contained and static.

The shorthand I’ve adopted for communicating this insoluble problem is a phrase: Time is the only Object; & everything else is a subject. It’s a proposition.

∞

Of course, on its face, the proposition is absurd. Who today can conceive of time as an “object,” a word or thought-form we attach to things, to material stuff in containment, to stand-alone pieces of the whole of everything? As we commonly assign “object” to the array of self-contained particles that make up our field of perception, it becomes counter-intuitive to think of “object” as time. We imagine the universe is the Everything. Alternatively, in some worldviews everything, including time, is situated in the corporeal omnipotence of the divine. The body of God is the encapsulation of All, including time, which is thought of then as the mechanism of unfolding the conception of the divine. The field of play for the divine is the Infinite, or timeless, and time is composed as a virtual subset, defining the character of the finite.

What it means to be living in time or alive in time for a finite being is thought of as a confinement in the machine of a sub-universal domain. To be subject to the universal is to be chronological. Only the profoundly timeless beings can know the nature of the everlasting, although humanity has adopted a special class of anomaly – those who are touched by or have endowed upon them a miraculous timelessness, which is correlated to the divine, the universal, the infinite. Often such beings are attributed with stories that describe the difficulties and conflict inherent in their condition, spanning the timeless and the finite. The half-breeds of the great schema of infinite and finite, such as saviors, saints, prophets and heroes, seem to be subject to a set of problems the rest of us can barely comprehend.

Dim Tim is a new version of halfling, and in my rendering of him he evades the routine of rigors that befall most of his precedent kind. To be fair to his divine and subjective precursors, Dim Tim is but a f®action. He is not (yet) materialized as himself, as a fact in operation amongst the living. Dim Tim is, like Prebble’s histories, only a “faction.”

∞

Dim Tim enters a historical moment or personage as a holographic overlay. Or he assumes identity so as to clarify the distinguishing character of the historical figure. The intervention is not a type of possession. Dim Tim inserts his data into the image playfully.

Categorization as an exercise is intertwined with man’s need to comprehend – and contain - time, space or place, the elemental or material, and the event. Within the architecture or through the lens of art, Dim Tim is an agent of representation, uncontained. What does he represent? As a figure in abstraction, which all of man’s need-to-comprehend is, Dim Tim stands for perception, as something in itself real, in terms of interactivity. Perception is participatory. The senses may be susceptible to illusion, but perception itself is real enough as a subjective phenomenon of sentient existence integrated in the unfolding of all, objective Time, which is not meaningfully divisive from locus and or the material that inhabits space. Art is art for humans, so the need for questioning the role of sentience in the applications of art is obviated. Dim Tim exists in the domain of the consensual, and it does not appear to be problematic for him to be thus de-limited. Dim Tim is homo indomitus, the unmanageable persona.

The distinction between real and illusion ceases to be an either/or conjecture. Dim Tim’s halfling nature blurs the line. Motion is the additive feature in his object-based reality, which has no issue with illusion. Everything moves, right? Dim Tim therefore is animated, a moving image. Embodied in the medium of paint, Dim Tim demonstrates the non-static nature of objects in relation to dimensional, 4D time, which, as Heidegger explained, is true time. I’ll leave off here, thinking of Dim Tim as a next generation Pogo, and what Dim Tim might reflect in our virtual/actual multiplied or dimensional selves.

… [end fragment]

AFTERWORD

DIM TIM: Chapter One, Fallacies of Hope is dedicated to Freidrich Kittler, who was one of my professors at European Graduate School. He has had a profound impact on my thinking about the digital, technical, communications, war, piece and drama. My favorite quote of Kittler’s, which is posted on the EGS website, is, “... it was a cock who every morning announced crummy weather.” I attended the 2010 lecture that produced the moment that yielded this magic bit of unintentional comedy. You have to watch the video for context.

Finding the right word never seems easy to me. Somehow this has everything to do with Dim Tim. I began sketching in Kittler’s lecture, my first at EGS, and continued to do so throughout my course in Saas-Fee, during the summers of 2010 and 2011. Notes on Dimensional Time is my pre-doctoral text. Dim Tim is a fragment of that body of thought, but not just. Painting is more than thought, more than language or information, memory, experience, more than life. This last – more than “life” – implies a subtle blasphemy, and requires its own thorough treatment. Not here and now.

Yet, a painting is so fragile, vulnerable to a thousand-thousand sorts of catastrophes, including aging. Kittler to me is a complex figure, one who personifies art, dimensionally. In my estimation, Kittler is a personage worthy of a memorial, a portrait. My attempt to represent the Kittler I encountered feels like a clumsy attempt to find the right word in a second, third or fourth language. This isn’t a good correlation, but there it is, nonetheless. Art and Kittler are both mountains (but not).

∞

Art, as such, is miraculous. At a break from instruction, I approached Badiou and asked for a moment. He generously complied. I basically said that when I began at EGS (Kittler’s was my first EGS seminar – Holy Smokes!), I was convinced that art needs philosophy. My question for Badiou was whether philosophy needs art. Emphatically, he said, today, philosophy needs art.

Fallacies of Hope,

Fallacies of Hope,  Paul McLean

Paul McLean